Expert Voices

Expert Voices

“You’re not going to get any traction with numbers like that around here!” It was early 2018 and I had just presented Vision Mobility’s latest future electric vehicle (EV) global sales forecast to senior management at a major OEM. The forecast of 30% of new car sales would be battery electric (BEV) by 2030, rising to 65% by 2040, was bullish for the time, but far from unreasonable given the data. While a little disappointed, I wasn’t entirely surprised at this conservative attitude towards progress.

Three and a half years later, the world has completely changed, and these numbers are looking conservative. In 2017, just after I presented my numbers, less than 1 million BEVs were sold, compared to a 4.4 million global forecast for this year.

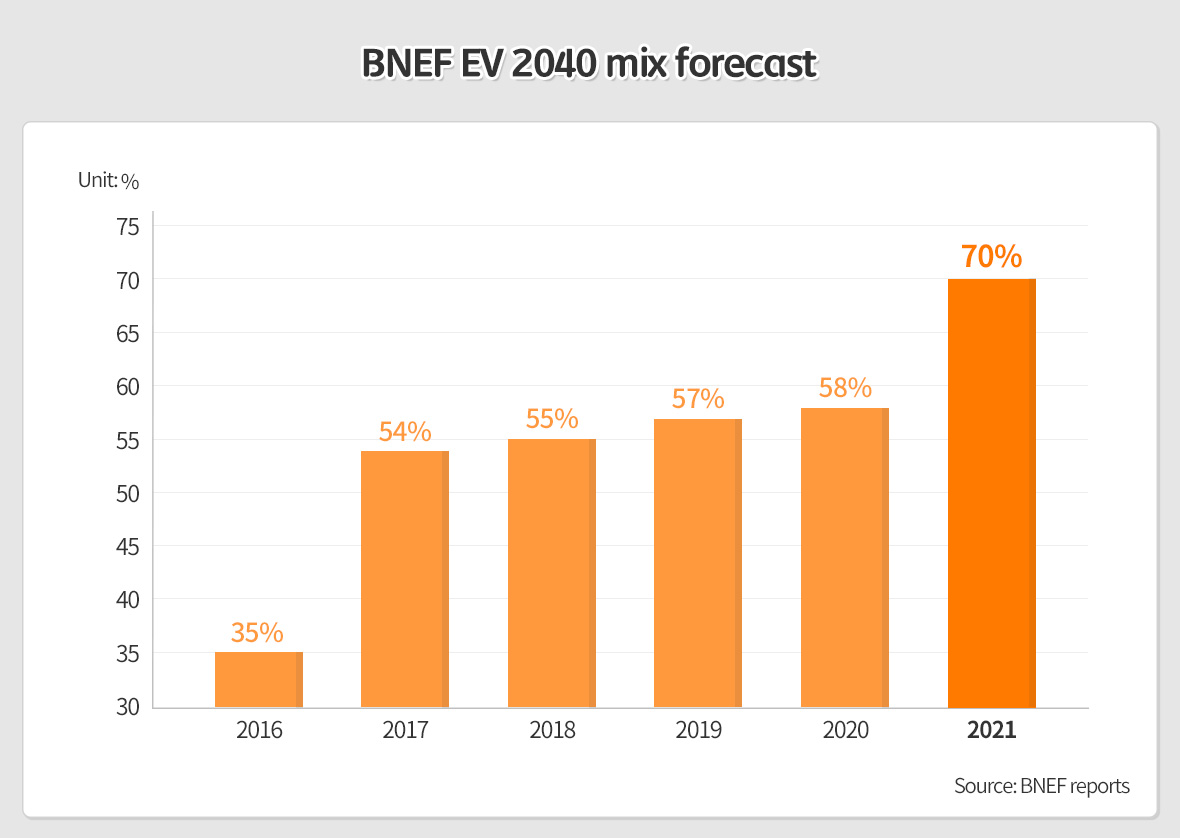

It’s not just Vision Mobility that is revising numbers upwards, well known analysts have a long history of going up. Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), perhaps the most bullish of the major analysts, are now forecasting 34% EV sales by 2030 and 70% by 2040 for cars, and 31% and 60% respectively for light commercial vehicles in their latest 2021 report, and up from just 35% in 2040, forecast in 2016.

There are three major reasons for the attitude change and revised forecasts: Tesla, Government policy, and COVID.

In early 2018, around when I compiled my forecast, Tesla was in the middle of what they called “Production Hell” – figuring out how to go from around 50,000 units in 2017 to almost 200,000 units in 2018 with the ramp up of Model 3, while bleeding cash at the same time. So, with just 1/200th the volume of Toyota and Volkswagen, it’s no wonder big OEMs weren’t taking Tesla too seriously.

Fast forward to today and Tesla profitability is strong and sales are on target to for 800,000 cars this year. Model 3 is now the world’s best selling luxury passenger car, and this September it became the number 1 selling vehicle in the UK, number 2 in New Zealand and was top 3 in several European countries.

What Tesla has done has inspired the rest of the industry, with many new models now coming out from almost all OEMs. Excellent EVs like the Ford Mustang Mach-E and Volkswagen ID4 have met with great reviews and long waiting lists, while the excitement in North America over the Ford F150 Lightning is palpable.

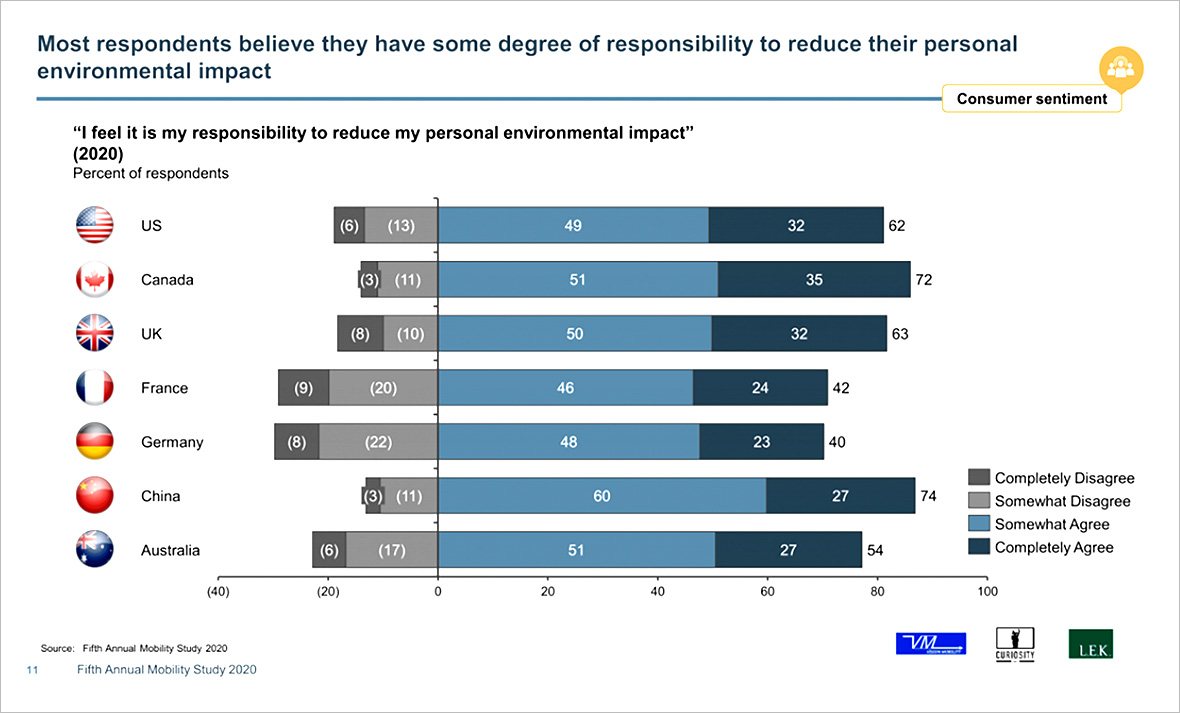

The global challenge of COVID has also had an outsized impact. In our Annual Global Mobility Study we found a very significant increase in consumer’s awareness of environmental issues over the COVID timing. People noticed cleaner air from less cars on the road, and there was a general rise in awareness that we have a personal responsibility to move away from fossil fuels and towards clean transportation and energy sources.

Source: “Fifth Annual Mobility Study 2020” by Vision Mobility, CuriosityCX and LEK Consulting

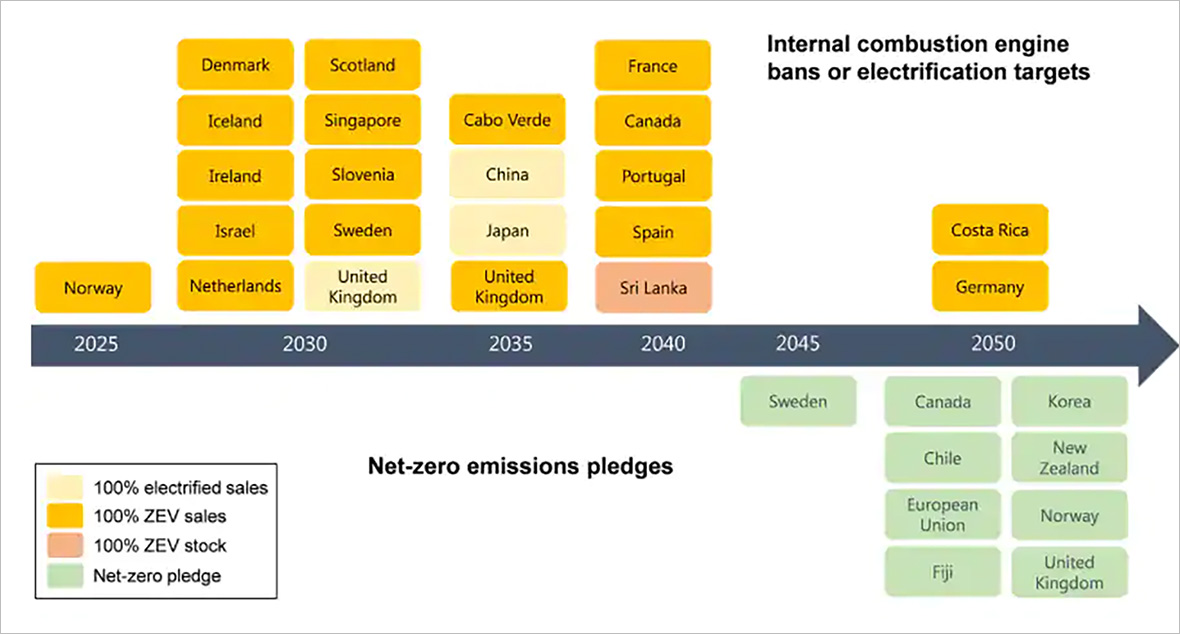

In that time, Government’s globally have reacted to changes in public environmental perceptions by introducing new regulations and mandates aimed at curbing internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles on the road. With transportation making up 20-30% of total CO2 emissions in most countries, and private transportation making up a majority of that, it is an obvious place to start.

Global pressures to adhere to the Paris agreement’s net zero targets and align policies towards making an impact are particularly being felt by automakers who are required to pivot R&D immediately towards Zero Emission Vehicles. What’s more, the rise in Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) considerations by major companies, especially deep pocketed investors, are ensuring that government commitments will be honored.

Source: IHS Markit

(Not shown in the graph above, the US has committed to 50% ZEV by 2030, and California to 100% light duty BEV by 2035, the second and the 5th biggest automotive markets globally.)

While these government bans on internal combustion engines globally represent SERIOUS future EV volume, the more important note is that they lock in future demand that has been building from consumer awareness and new product releases.

What the above demand forecasts mean is that somewhere between 25 million and 38 million new EVs will need large batteries in 2030, and 70 million to 80 million batteries by 2040. Compared to hybrids, EV batteries are much larger. While a hybrid might have a battery of around 1.5kWh, and a plug in hybrid around 15kWh, most EVs have 50kWh and 100kWh battery packs, with the new generation of electric pickups likely to be as large as 200kWh. This means that the global production of battery cells must rise very quickly to meet demand.

However, there are barriers on supply side that threaten the continued rise of electric vehicle sales, primarily around battery supply chain. While globally there is an abundance of minerals to support future battery growth, the pathway from mine to vehicle is not easy. Geopolitics plays a part, as well as sustainable mining practices, ore processing and battery production skills. Fortunately, many of the key minerals, like nickel and lithium, are found in stable resource economies like Australia and Canada, but mines and processing plants take time to develop and prepare for production to enable customer orders to be fulfilled.

Recently, JB Straubel, the former CTO of Tesla and now CEO of battery recycler Redwood Material had this to say:

“So many OEMs (automakers), countries, factories, and customers are leaping into EVs and making huge announcements about going full electric this decade or next, but I don’t think that they have done the math fully when it comes to what it entails in the supply chain and tracing it all the way back to the mines … I do think we are going to have a really painful time at it. It’s not going to be just a battery shortage, it is going to ripple through the whole supply chain.”

In other words, guaranteeing that all the pieces are in place for battery manufacturing and supply is critically important. As EVs take off by entering the minds of mainstream consumer consciousness, and we’re already seeing long waiting lists today, demand could quickly exceed supply if supply chains are not in place to handle the expected volume. Large and established battery companies, like SK Innovation, offer established pathways to critical mineral supplies and ore processing, and this is a factor that all potential buyers must consider.

What’s more, company’s like Straubel’s Redwood Materials and SK Innovation have developed cutting edge battery recycling technologies that can assist in the supply of critical minerals and metals. This creates a holistic, sustainable virtuous cycle that can contribute directly to more battery production, thereby snowballing the impact.

From our side as automotive industry analysts, we see EV demand as strong with broad based support, while Government regulation and investor ESG requirements ensure it will remain this way. However, it’s the supply side for batteries that presents the biggest challenge moving forward. It’s not for a lack of raw materials or technology, the bottle neck is production capacity, and the time needed for this to establish to meet demand.

It is this that will limit our collective ability to supply low cost batteries for vehicles that meets consumer’s requirements. Lack of battery supply keeps EV prices high and caps demand, especially in the mainstream sector of the market. What this means is that the ability to decarbonize our planet and reduce toxic smog in our cities may take longer than we hoped.

I am personally very hopeful that these supply challenges will be dealt with and growth of EVs can quickly continue. After all, we have only one planet and one set of lungs, and I don’t wish to damage either.

– The North American pickup juggernaut is going Electric

Youtube

Youtube Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Linkedin

Linkedin